How COVID-19 Changed American Life: Looking Back 5 Years Later

Most Americans say the pandemic drove the country apart

The most significant pandemic of our lifetime arrived as the United States was experiencing three major societal trends: a growing divide between partisans of the left and right, decreasing trust in many institutions, and a massive splintering of the information environment.

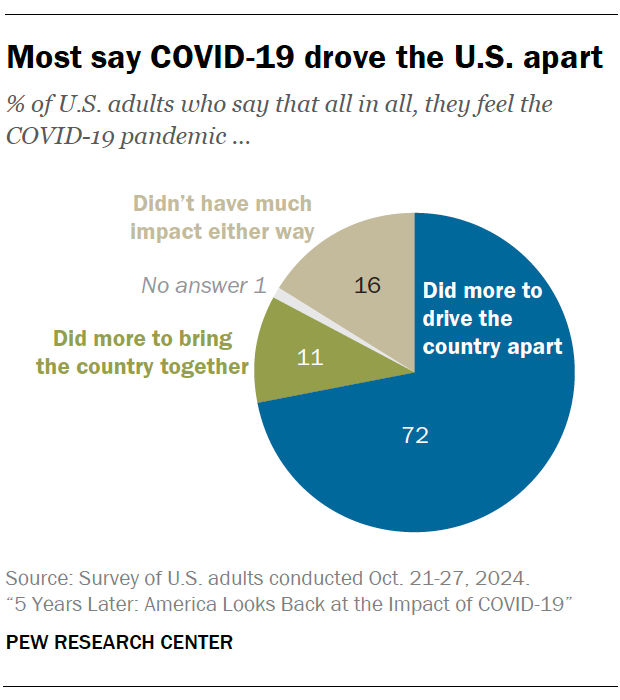

COVID-19 did not cause any of this, but these forces fueled the country’s divided response. Looking back, nearly three-quarters of U.S. adults (72%) say the pandemic did more to drive the country apart than to bring it together.

Fundamental differences arose between Americans over what we expect from our government, how much tolerance we have for health risks, and which groups and sectors to prioritize in a pandemic. Many of these divides continue to play out in the nation’s politics today.

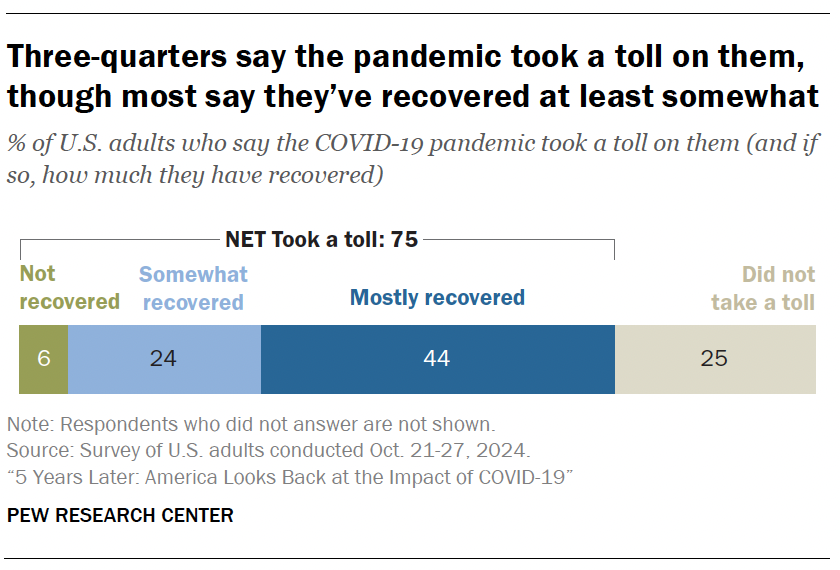

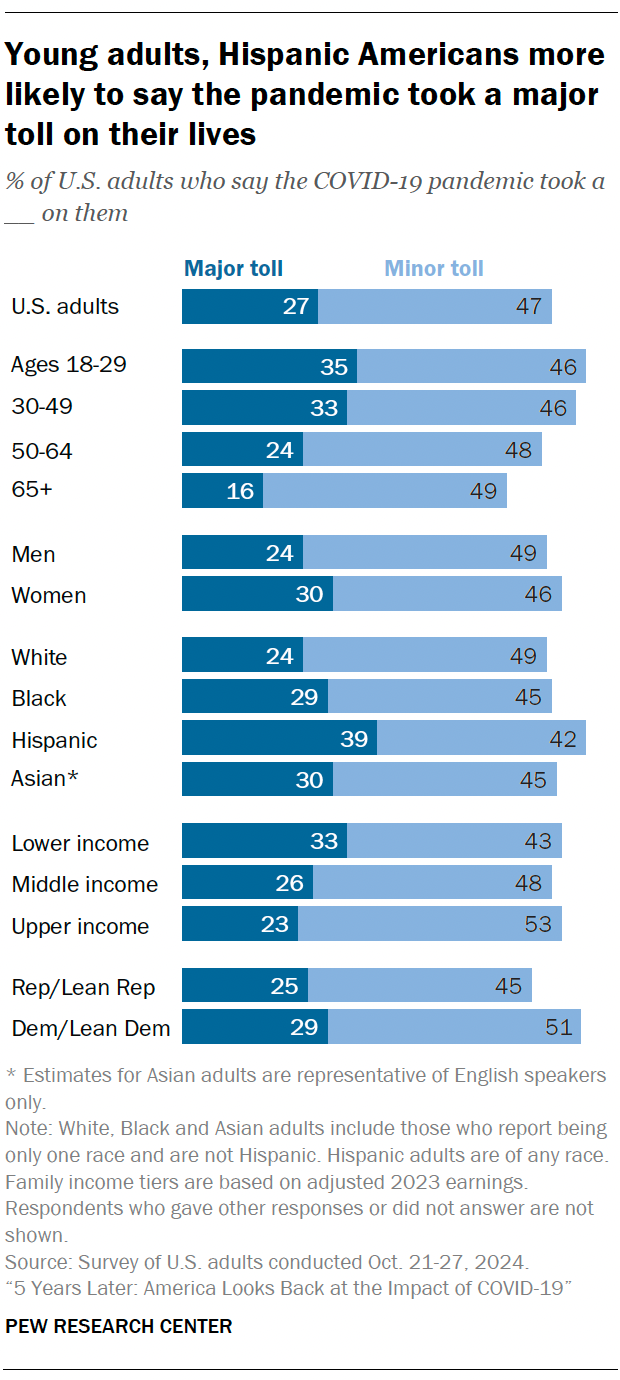

The pandemic left few aspects of daily life in America untouched. Looking back on it nearly five years later, three-quarters of Americans say the COVID-19 pandemic took some sort of toll on their own lives. This includes 27% who say it had a major toll on them and 47% who say it took a minor toll.

The virus itself also had a staggering impact. A large majority of U.S. adults have had COVID-19 at some point, and more than 1 million Americans died from it. Millions continue to struggle with long COVID. And most say they know someone who was hospitalized or died from the virus.

But most Americans have moved on. The vast majority of those who say their lives were impacted report having recovered at least somewhat. Among U.S. adults overall, about one-in-five (21%) now say the coronavirus is a major threat to the health of the U.S. population as a whole. And a majority (56%) think it’s no longer something we really need to worry about much.

This is reflected in Americans’ behavior: Just 4% regularly wear a mask, while most never do. And fewer than half of U.S. adults said they planned to get an updated COVID-19 vaccine last fall, a stark contrast to the long lines and widespread demand that met the initial rollout of vaccines.

At the five-year anniversary of the coronavirus outbreak, a major Pew Research Center survey conducted in late October 2024 provides insight into how Americans assess the nation’s pandemic response. These findings are paired with an analysis of trends dating to early 2020. The report sections take a closer look at COVID-19’s impact in four specific areas of American life: health, work, religion and technology.

Massive gaps remain between Republicans and Democrats in views toward COVID-19, including vaccines

Majorities of both Democrats and Republicans were personally impacted by the pandemic: Eight-in-ten Democrats (including independents who lean to the Democratic Party) say COVID-19 took at least a minor toll on them, while 69% of Republicans and GOP leaners say the same.

And virtually identical shares of Republicans and Democrats say they have tested positive for COVID-19 or been pretty sure they had it.

But the pandemic highlighted the different values and priorities of America’s two major political parties.

Two years after the pandemic started, Republicans were more likely than Democrats to say the country had given too little priority to individual choice and supporting businesses and economic activity in the response to the coronavirus outbreak. And a larger majority of Republicans than Democrats said the country hadn’t given enough priority to the needs of K-12 students. Democrats, meanwhile, were more likely to say the country came up short on limiting risks for vulnerable populations and protecting public health.

These differing outlooks are part of what shaped the sharply partisan responses to COVID-19 that persist today.

In the new survey:

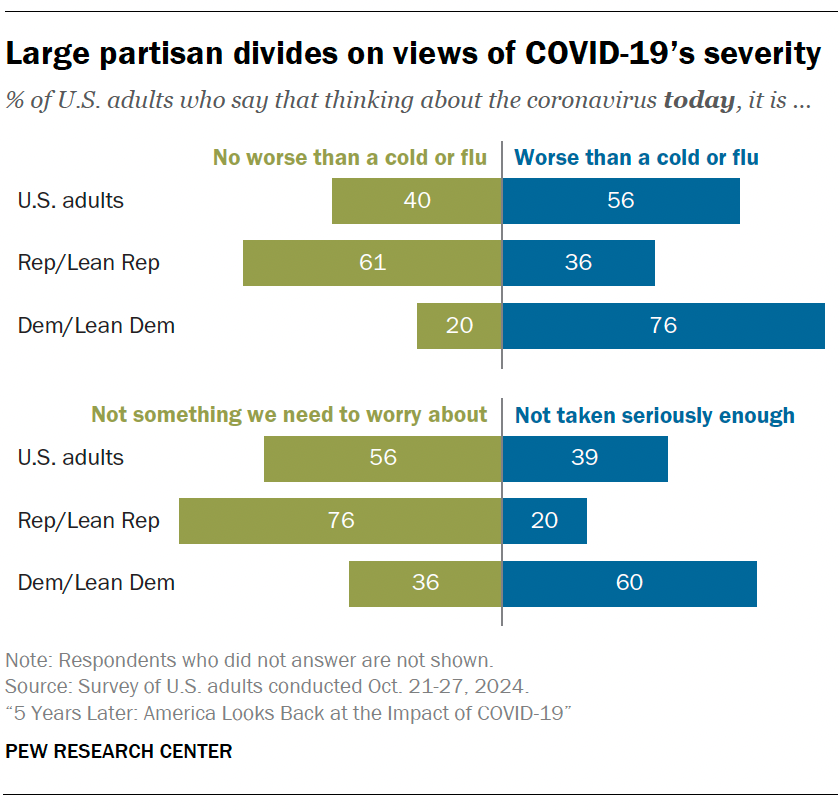

- Republicans are much more likely to say COVID-19 is now no worse than a cold or flu. About six-in-ten Republicans say this. By contrast, 76% of Democrats take the opposite view and describe COVID-19 today as worse than a cold or flu.

- Meanwhile, Democrats are much more inclined to worry that we’re not taking COVID-19 seriously enough today. Fully 60% of Democrats worry we’re not taking COVID-19 seriously enough now, compared with 20% of Republicans.

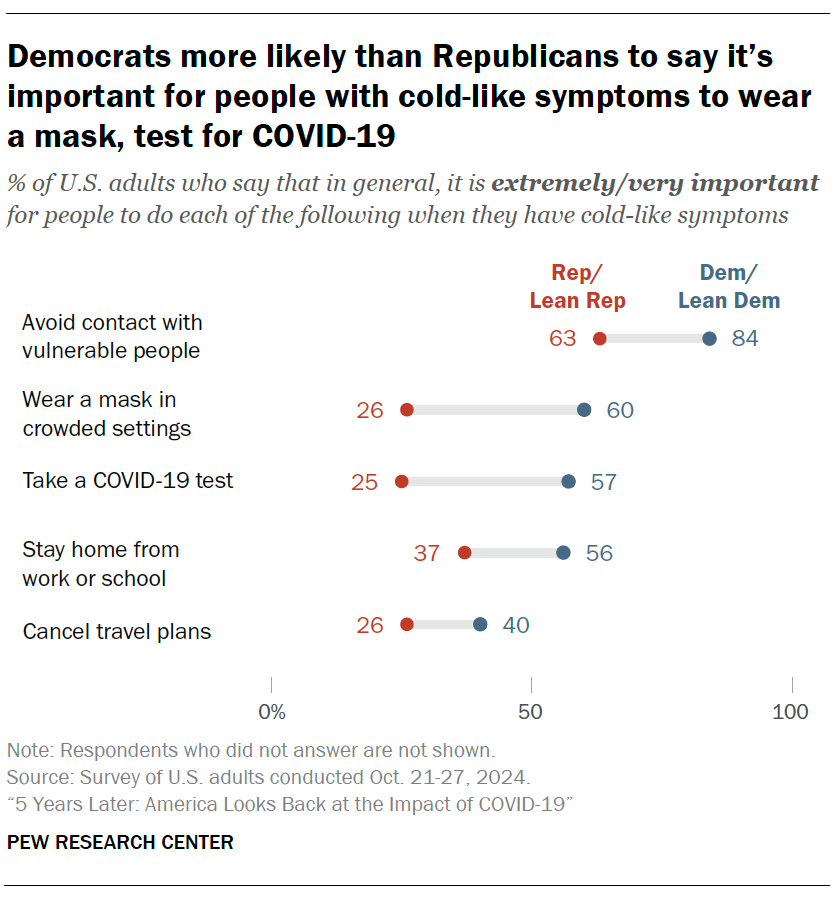

- There also are differing views on the steps people should take when they are feeling sick. While majorities of both parties say it is extremely or very important for a person with cold-like symptoms to avoid contact with vulnerable people, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to express this view (84% vs. 63%). Democrats also are much more likely than Republicans to say it’s crucial for someone with these symptoms to stay home from work or school, wear a mask in crowded settings and test for COVID-19.

Views of vaccines in the COVID-19 era

The rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines was an unprecedented achievement for science and medicine that experts say saved millions of lives around the world. Large shares of U.S. adults lined up to get vaccinated in the pandemic’s first year.

- By last fall – with risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19 far lower than at the height of the pandemic – most Americans said they probably would not get the most updated version of the COVID-19 vaccine. And the stark partisan differences in vaccine uptake seen throughout the pandemic remained wide. About eight-in-ten Republicans (81%) said they probably wouldn’t get an updated vaccine. By contrast, a majority of Democrats said they were planning to get it (39%) or had already received it (23%).

- Among those ages 65 and older, 70% of Republicans said they were unlikely to get the newest vaccine, while more than eight-in-ten Democrats said that they had already gotten it (42%) or probably would (42%).

In a 2023 survey, Americans expressed lukewarm views of the preventative health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines, along with concerns about side effects.

Health officials worry that currents of skepticism toward COVID-19 vaccines could cross over into views of other vaccines, like the one given to children for measles, mumps and rubella (MMR). A March 2023 Center survey found large shares of U.S. adults continued to view the benefits of the MMR vaccine as outweighing the risks, but support for policies requiring vaccines for children to attend public schools had fallen 12 percentage points, a drop driven almost entirely by falling support among Republicans.

And data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that there has been a downtick in the share of kindergarteners with complete vaccination records for measles and other diseases, including polio and chickenpox.

Did the nation’s leaders and institutions meet the moment?

With the benefit of five years of perspective, Americans offer a mixed assessment of how their leaders and institutions responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. Those on the front lines – hospitals and medical centers – stand out for the positive ratings they receive for their performance.

- About half of U.S. adults or fewer now say their state elected officials (49%), Joe Biden (40%) and Donald Trump (38%) did an excellent or good job responding to the pandemic. A slim majority (56%) give positive ratings to public health officials, like those at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- Only local hospitals get a full-throated approval from Americans: Looking back, 78% say medical centers in their area responded well to the pandemic.

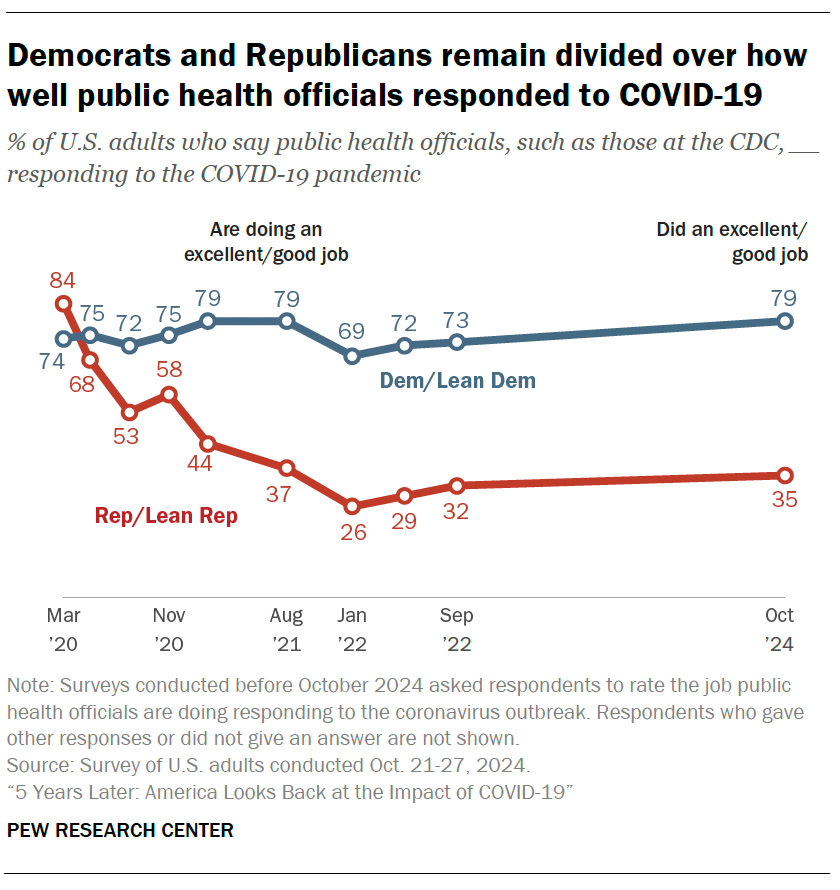

- Again, there are huge partisan differences on several of these questions. For example, 79% of Democrats say public health officials’ response was excellent or good, while 35% of Republicans agree. Republicans’ positive ratings of public health officials fell 58 points between spring 2020 and the start 0f 2022.

Restrictions on public activity were a central component of officials’ response to the pandemic across levels of government.

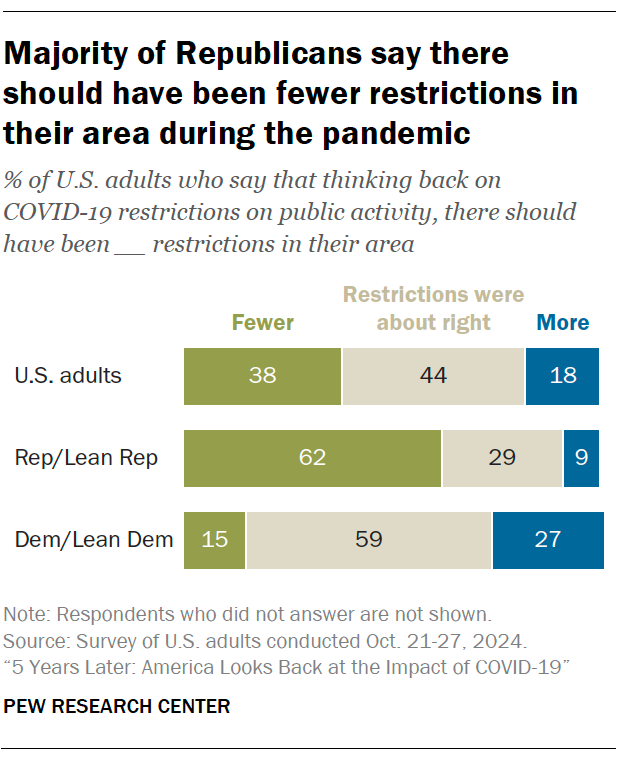

Asked about their assessment today, fewer than half of U.S. adults (44%) say the restrictions on public activity in their area during the pandemic were about right. Another 38% say there should have been fewer restrictions in their area, while 18% say there should have been more.

At the beginning of the pandemic, most Democrats and Republicans agreed with newly implemented restrictions on public gatherings and nonessential businesses. But these views changed quickly as the pandemic wore on, with continuing impacts on the economy, schools and other aspects of daily life. Republicans, in particular, became increasingly critical of activity restrictions.

- Now, looking back, 62% of Republicans say there should have been fewer restrictions on activity in their area, while just 15% of Democrats share this view. A majority of Democrats (59%) think their local officials got it about right, but about a quarter say there should even have been more restrictions than there were.

- When it comes to K-12 public schools, 55% of Republicans say schools in their area stayed closed for too long, while just 17% of Democrats agree. About half of Democrats (49%) say schools in their area were closed for about the right amount of time.

More broadly, the outbreak cast a spotlight on the role of scientists and scientific information. During the pandemic, Americans’ confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interests fell: 87% expressed at least a fair amount of confidence in April 2020, but that number dropped to 73% in October 2023. This overall decline was driven by a sharp drop in the share of Republicans who express confidence in scientists to act in the public interest (from 85% to 61%).

Jump to more details about Americans’ views on the virus’ health effects and the public health response.

The information environment: Many say the media exaggerated the risks of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic forced Americans to try to parse through information about a new topic that scientists were scrambling to fully understand – and that almost no one had heard of just a few months before. About two years into the pandemic, 60% of U.S. adults said they felt confused as a result of changes to public health officials’ recommendations, and 57% said false and misleading information about the virus and vaccines contributed a lot to problems with the response.

Challenges in public understanding persist even today, with about four-in-ten Americans – including similar shares of Democrats (36%) and Republicans (41%) – saying they are not sure what the current health guidelines are for someone who gets COVID-19.

COVID-19 also arrived in a rapidly changing news environment. Many Americans had already lost trust in the information from national news organizations – a change driven by Republicans. And news about COVID-19 fit into that trend:

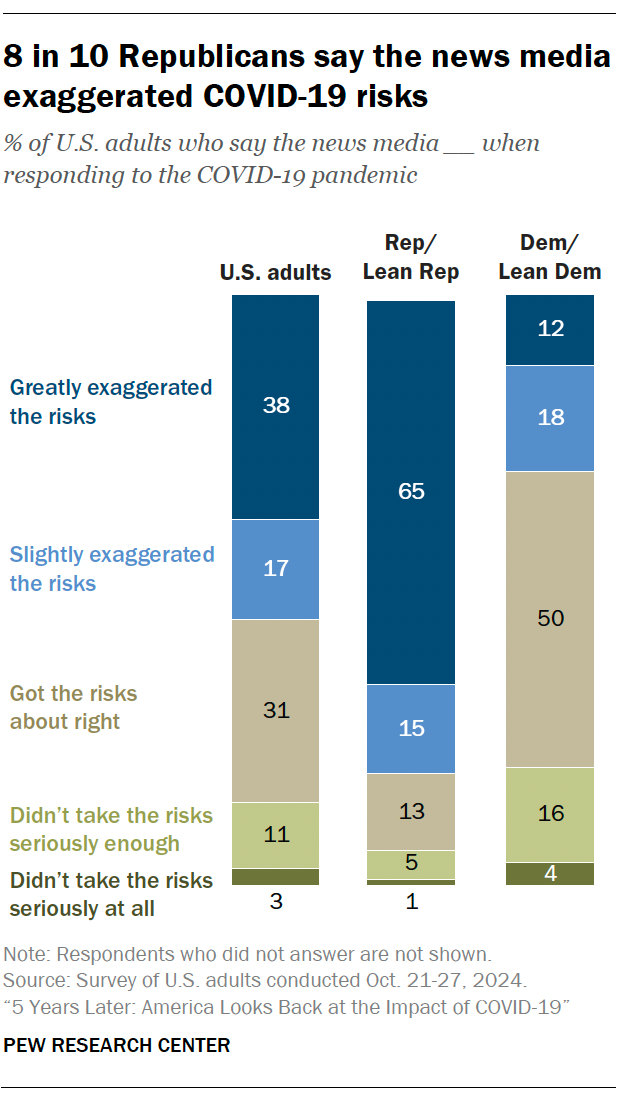

- Overall, 54% of Americans say the news media exaggerated the risks of COVID-19 at least slightly. This includes eight-in-ten Republicans who say the media greatly (65%) or slightly (15%) exaggerated the risks, compared with three-in-ten Democrats who express similar views. An additional two-in-ten Democrats say the media didn’t take the risks seriously enough, while half say they got the risks about right.

- There are similar patterns in views toward public health officials like those at the CDC, Joe Biden and his administration, and state elected officials. In each case, Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to say these sources exaggerated the risks of COVID-19 at least slightly.

- Republicans have a different perspective on what they heard from the Trump administration: More than half of Republicans (59%) say Trump got the risks about right. By contrast, 81% of Democrats say Trump didn’t take the risks of COVID-19 seriously enough.

- At the same time, Republicans are much less confident than Democrats that they would be able to find accurate information in the event of a new health emergency. While about three-quarters of Democrats (74%) say they are at least somewhat confident they could do this, just under half of Republicans (46%) agree. Overall, 60% of U.S. adults express this view.

COVID-19 affected different groups of Americans in different ways

Adults under age 50 are more likely than their elders to say COVID-19 took a major toll on their lives – and to say they haven’t yet fully recovered from the pandemic. Many people in this younger group were finishing their schooling years or parenting young children when the pandemic hit. Still, the vast majority of people who died from COVID-19 in the United States were ages 50 and older, underscoring the range of health and social impacts COVID-19 had on Americans.

Women and Hispanics also are more likely than men and other racial and ethnic groups to say COVID-19 had a major impact on their lives. And Americans with lower incomes report suffering a major toll at a higher rate. Several data points from the pandemic highlight the differential impacts COVID-19 had on Americans:

- In the early days of COVID-19, young adults were living with their parents at the highest levels since the Great Depression.

- Among adults 25 and older who have no education beyond high school, more women left the labor force during the pandemic than men. And at multiple points during the pandemic, working mothers with children under 12 were more likely than working fathers in this category to say it was difficult to handle work and child care responsibilities.

- About half of Hispanic adults (49%) said in March 2021 that they or someone in their household had lost a job or taken a pay cut because of the pandemic, higher than the share of U.S. adults overall who said the same. Younger adults also were more likely to experience job loss or pay reduction.

The pandemic also hit Black and Hispanic communities disproportionately hard in terms of mortality rates in the first year after the outbreak. And Black Americans remain much more likely than their White counterparts to say that COVID-19 remains a major threat to the health of the U.S. population today.

Work, technology and religion: What changed, and what didn’t, about American life amid COVID-19

The pandemic impacted many aspects of life in a variety of ways. Some people have gotten new flexibility when it comes to work and religious worship as technology has gained a new role in many Americans’ lives. But the pandemic also highlighted societal disparities in things like access to technology and the option to work remotely.

The way we work

The pandemic created a seismic shock in the labor market, with Hispanic people, young adults and low-wage workers hardest hit.

In the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak, a majority of American workers (62%) had jobs that couldn’t be done from home. But for those who could telecommute, the pandemic ushered in an era of increased remote work that continues to this day.

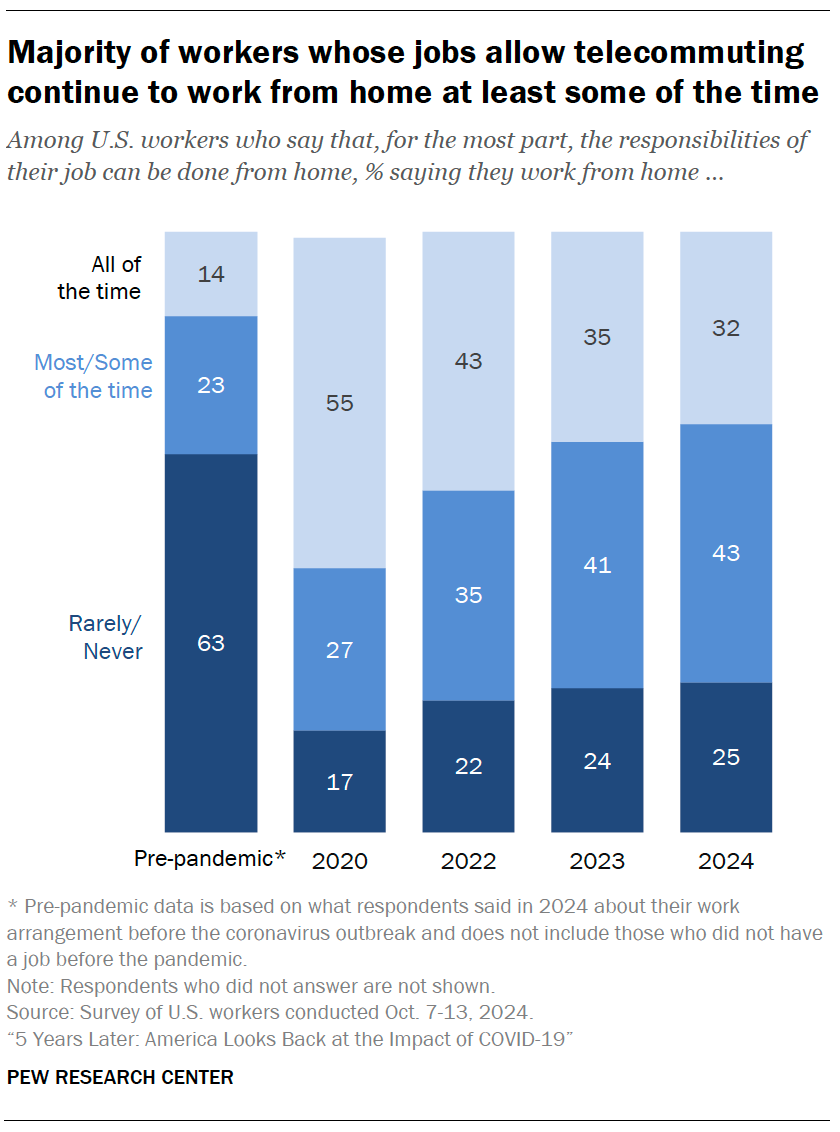

- Among American workers whose jobs currently allow for remote work as a possibility, 14% say they were working remotely all of the time before the pandemic.

- During the first year of the pandemic, that number peaked at 55% in October 2020.

- Today, 32% of these workers still say they are working remotely all the time.

- Among workers whose jobs currently allow for remote work, 23% say they were working from home most or some of the time before the pandemic, while 43% say this is the case today.

Many remote or hybrid workers say they prefer to work from home. And the shift to telework (and hybrid schedules) has had one clear upside for workers: Most of them say it has helped them balance their work and personal lives. But the biggest downside for these workers is that many say they feel less connected to colleagues.

Jump to more details on how COVID-19 changed work in America.

Religious worship

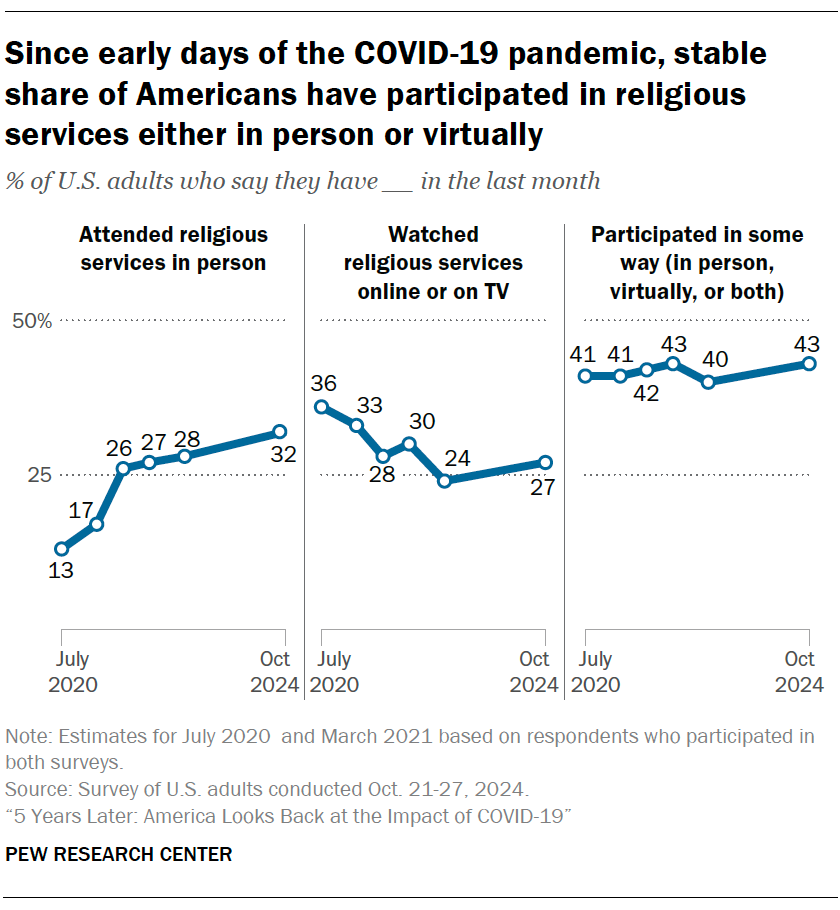

COVID-19 drastically changed how Americans participate in worship services. In July 2020, just 6% of Americans who attend services at least monthly said that their house of worship was open to the public and operating like normal. Like remote work, the share of Americans who report watching religious services online or on TV peaked early in the pandemic, with 36% saying they participated virtually in the last month as of July 2020. And many are still doing so today.

But the pandemic did not shake American religion: The share participating in services in some way has been steady, and the share who say COVID-19 had a big impact on their spiritual life is small.

Jump to more details on how COVID-19 affected religious worship in America.

General technology use

The internet was critical to Americans during the pandemic, with 90% saying it was important to their life at the time (as of April 2021) – including 58% who said it was essential.

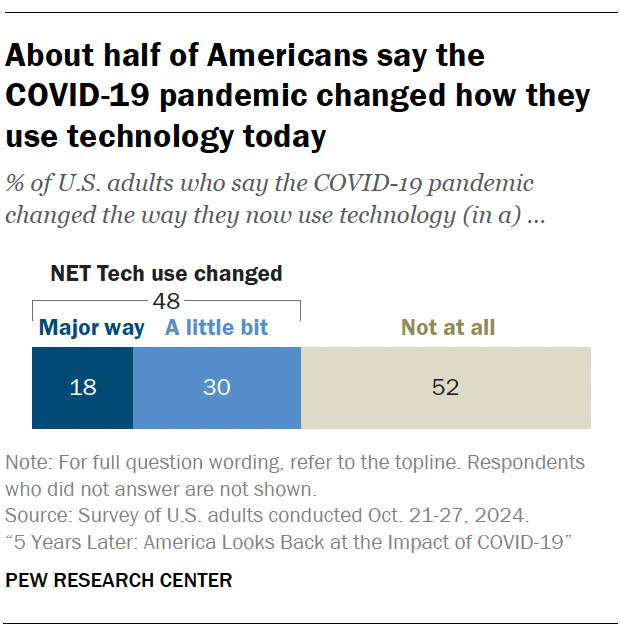

Looking back on the pandemic today, about half of U.S. adults say it changed the way they now use technology, with younger people especially inclined to say this.

The pandemic also intersected with long-standing digital divides, and in many ways brought them into the spotlight. For example, we’ve long seen differences by income in who has access to technology. And during the pandemic, lower-income teens were more likely to report tech-related challenges with schoolwork, such as needing to complete homework on a cellphone or over public Wi-Fi.

Among Americans who say COVID-19 changed the way they use technology, those with lower incomes are less likely to say these changes have made their lives easier (in October 2024). Still, the largest shares regardless of income say these changes have made their lives both easier and harder.

Jump to more details on how COVID-19 changed technology use in America.

Looking ahead: Are we ready for the next health emergency?

Americans’ expectations for the nation’s response to a future health emergency appear somewhat positive compared with the critiques and divisiveness they associate with the coronavirus response.

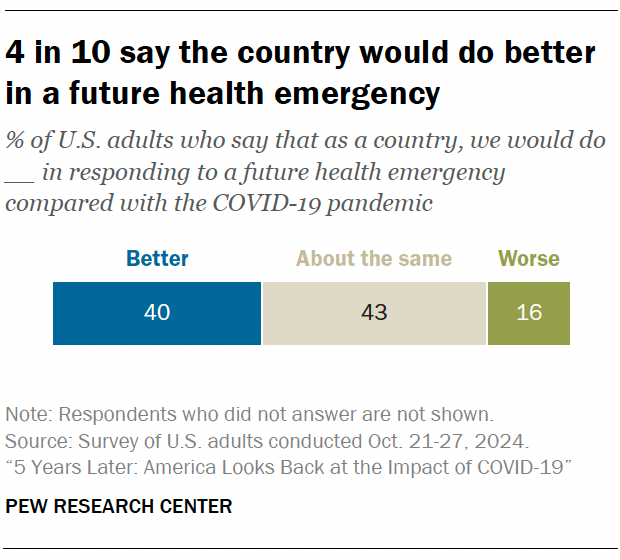

More than twice as many say the U.S. would do better with a future health emergency (40%) than say we would do worse (16%), though many Americans (43%) say we would do about the same as we did with how the country handled the COVID-19 pandemic.

About six-in-ten (61%) think the public health system would do at least a somewhat good job dealing with a future health emergency; an even larger share (69%) think people in their own community would do a good job.

A larger share of Democrats (73%) than Republicans (50%) think the public health system in the U.S. would do a good job dealing with a future health emergency. But comparable majorities of both Democrats (72%) and Republicans (68%) express confidence in their own communities to respond well.